If you are researching ways to keep your aging brain agile, don’t overlook exercise! That idea makes perfect sense.

Exercise is probably one of the most recommended solutions for every physical and mental health-related problem globally. This is for a good reason! The research into exercise’s benefits is wide-ranging and detailed, showcasing its effects on fitness, disease risk, positive thinking, and more.

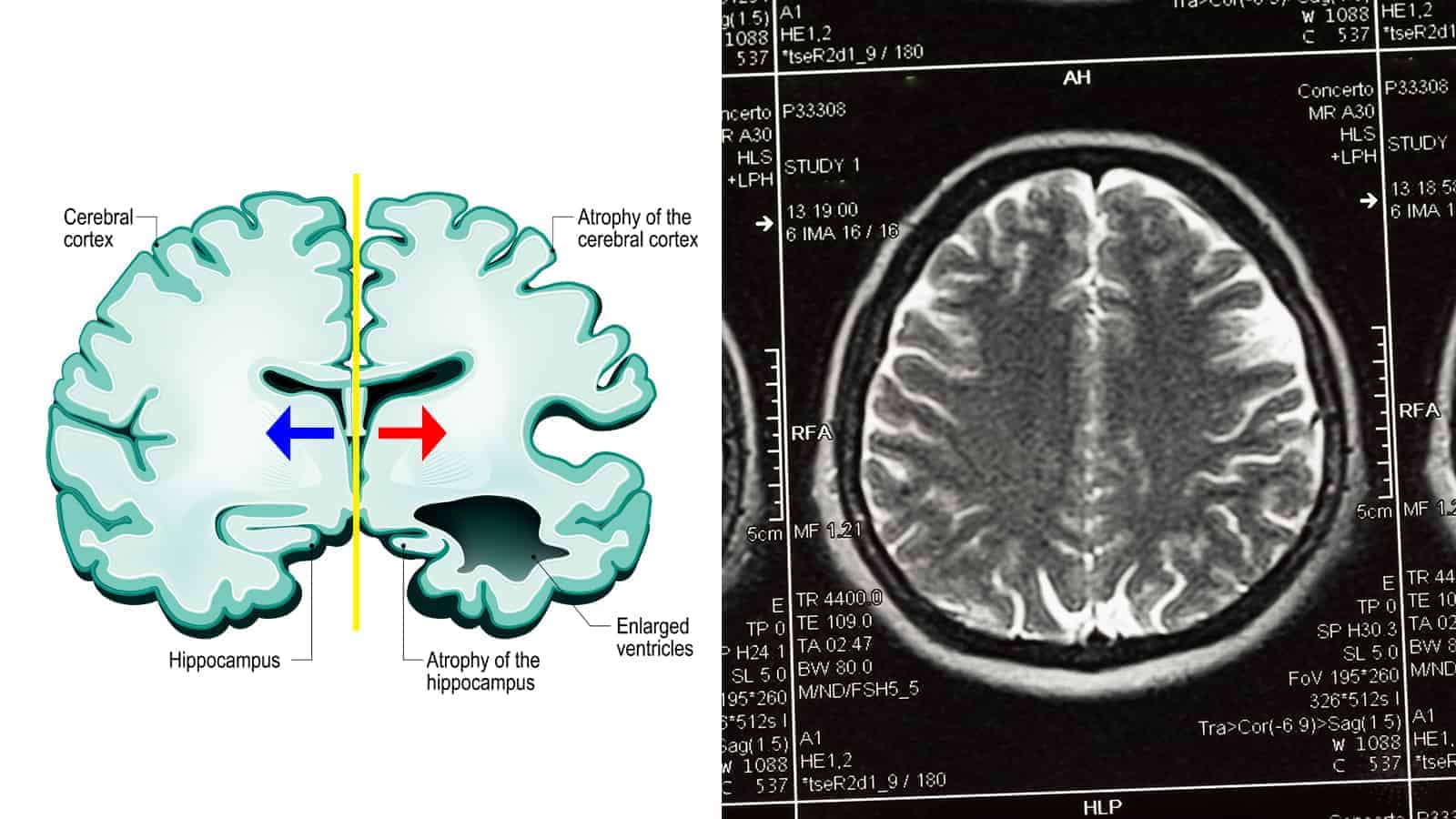

But what about the brain? Specifically, what about cognitive decline? Anyone who has seen the effects of mental impairment due to age knows that it often seems and feels unstoppable, so it can be a little strange to think that exercise can prevent it.

So, can exercise help aging brains stay healthy? Research says so! Here are some findings that provide insight into the complex subject of cognitive degeneration and its links to physical activity.

1. Exercising Helps Aging Brains

For a long time, people have touted exercise as a simple, foolproof solution to the ever-approaching threat of cognitive decline and the effects of an aging brain. For the elderly who are already dealing with some brain aging, this appears to be true.A randomized control study titled “Acute Exercise Effects Predict Training Change in Cognition and Connectivity,” published in the Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise journal in 2020, provides positive insight into this subject. The National Institutes of Health’s National Institute on Aging funded this study. Here are some details regarding the paper:

- The trial was relatively small, involving only 34 elderly individuals aged 60 to 80.

- All participants were not regular exercisers but were otherwise healthy during the experiment.

- Multiple trials involved brain scans, working memory tests, and physical activity.

- The study built on previous research regarding the mental boosts provided by exercise, especially given the contradictory results of earlier experiments.

The study’s methods were as follows:

- Participants rode on a stationary bike twice, once each on separate occasions. The first occasion involved light resistance, and the second involved more strenuous workouts. Both rides lasted 20 minutes.

- Before each bike ride and after, participants underwent memory tests and brain scans.

- The brain scans sought to concentrate on regional activity bursts in the brain, specifically in areas known to share and collect memories.

- Researchers administered working memory tests, giving each participant a flashcard-type quiz on a computer screen. The trial involved rotating adult faces – eight in total – that switched every three seconds. Participants then matched two cards to one previously seen.

- The same participants were split into two groups and assigned 12 weeks of regular exercise training and a stationary bike. The exercise involved 50 minutes of pedaling thrice weekly.

- One group was told to do lighter workouts, while the other was told to do moderate-intensity workouts.

The study results:

The results of the study were simple but obvious. Participants experienced noticeable cognitive benefits from just one exercise session. Those benefits seemed on par with those achieved by participants who performed regular exercise over more extended periods. This provides a positive outlook for those who don’t exercise regularly or simply can’t. Here are some specifics about the results:

- Some participants had significant regional connectivity in their brains between the prefrontal and parietal cortices after just one exercise session. The areas mentioned are responsible for memory and cognition-related functions. Others did not experience this change.

- Those who had the regional connectivity improvement also performed with more accuracy on the memory tests conducted.

- The improvement in the aforementioned regional connectivity experienced benefits for only a short time, indicating immediate but brief benefits.

- With long-term exercise, most participants experienced the aforementioned regional connectivity benefits. But it was no different to the one-time, short exercise benefits.

Takeaways on helping aging brains:

- The benefits to short exercise are clear, but they are temporary, necessitating regular action to continue providing effects.

- Benefits of long-term exercise routines are more consistent, but they’re not better than short exercise.

- Both short and long-term exercises have similar cognitive benefits to aging brains, but long-term exercise routines allow for the benefits to last.

- Further research is necessary to understand why not everyone can benefit from exercise sessions.

- Further research that includes those with beta-blockers and chronic health conditions will likely have different results.

2. Moderate Exercise Is Best

Simple exercises are great for those with mobility issues and are an easy way to get exercise into a busy routine, but they’re often too gentle for tremendous results. And, of course, intense exercises are fantastic for strength-related results, but they’re less convenient and may not even be possible for those with aging brains. Moderate exercise is, therefore, the apparent winner for those who want to work out to fight cognitive decline.

Luckily, it turns out that science indicates that moderate exercise is the most effective way to keep an aging brain healthy as time goes on.

These findings are central in a study called “One-Year Aerobic Exercise Reduced Carotid Arterial Stiffness and Increased Cerebral Blood Flow in Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment,” published in 2021 in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. It built off of a study from 2020 titled “Brain Perfusion Change in Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment After 12 Months of Aerobic Exercise Training” in the same journal.

About the study

The study revealed that moderate-to-vigorous physical activity has positive effects on a slowly aging brain in two ways that simple, relaxed exercise is not. Before we delve deeper, here are some details regarding the paper:

- The study is a randomized controlled trial with 48 participants aged 55 years to 80 years old with specific symptoms of an aging brain.

- The study lasted for a year and split participants into two groups.

- One group of participants underwent a regimen involving moderate-to-vigorous aerobic exercise. They were to perform it for 30 to 40 minutes, thrice to five times weekly.

- Another group of participants underwent simple, non-cardio stretching and toning workouts. They were to perform it for 30 to 40 minutes, thrice to five times weekly.

- The study aimed to determine how cerebral blood flow and central arterial stiffness were affected by aerobic exercise training in elderly individuals with beginning signs of cognitive decline, specifically amnestic mild cognitive impairment.

- The team monitored both groups over the year.

- CVLT-II and D-KEFS, both standard and commonly used neuropsychological tests, were used to measure improvement and change.

The findings:

Findings were reasonably straightforward, indicating that the group that performed moderate-to-vigorous aerobic exercise enjoyed much better benefits to their brains than those who did stretching. Here are some more detailed findings:

- Participants who did moderate-to-vigorous exercise benefited from increased cerebral blood flow to and in their brains. They also experienced a lower level of central arterial stiffness, which refers to the blood vessel stiffness in the neck.

- When oxygen consumption, a standard indicator of overall aerobic fitness, increased in participants, their benefits increased.

- Those who stretched and did gentler exercises did not experience any of these changes at all.

- According to researchers, no participants experienced improved executive functions or episodic memory, which may take longer than a year of exercise to develop.

- Gentle stretching does have physical well-being benefits but likely is not as crucial in maintaining the health of an aging brain.

3. In Middle Age, It May Not Matter

It’s commonly said that the sooner one begins exercising, the more positive the benefits will be when you grow older. Unfortunately, this may not be the case, according to a 2021 study involving 2,000 women.

The research paper, “Longitudinal Assessment of Physical Activity and Cognitive Outcomes Among Women at Midlife,” was published in JAMA Network Open. Here are some details regarding the paper:

- The study lasted over the course of twenty years.

- The participants were 2,000 middle-aged women with an average age of 45.7 at the beginning of the experiment.

- The study aimed to assess whether physical activity could affect women’s cognitive outcomes in later life in a longitudinal manner.

- The areas of cognitive ability measured were verbal memory, processing speed, and working memory.

The findings:

The study had interesting findings that were contrary to what was likely expected. Most people generally agree that exercise provides neuroprotective benefits, but the results of this study indicated that it has little to no effect. In fact, the study authors suggest that the common belief stems from reverse causation instead of any actual concrete evidence.

Naturally, as with all areas of research, this study has its limitations. This study specialized in self-selected exercise and its ability to slow neurodegeneration and cognitive aging. It is still possible that increasing physical activity, using specific exercises, or uniquely adapting physical activity type may have different effects on aging.

The current goal following this study lies in learning to stall cognitive aging beginning in the middle ages of one’s life. For now, there is no confirmed way to do so, but physical activity still provides plenty of well-being benefits that are useful regardless. Even if it doesn’t prevent the aging of a brain, its other effects are well-worth exercising for.

Final Thoughts On Some Ways Exercise Can Help Aging Brains Stay Healthy

Let’s get one thing straight. All exercise, no matter what kind, if done without physical injury, benefits you in some way, shape, or form. This can be via increasing positive thinking and mood, improving fitness, helping the cardiovascular systems, and much more. But just because exercise is always good for you, that doesn’t mean it’s always assisting every part of the body.

The brain is a complicated organ, and cognitive degeneration is a complex topic. Then, it makes sense that only specific kinds of exercise may be the most beneficial to an aging brain, especially in the fight against degenerative disorders and other forms of mental decline and impairment.

As you age, you should be doing some exercise to give your body the help it needs to maintain a healthy and positive state. But if you’re interested in fighting the aging of your brain, try to tailor your exercise choices. For example, opt for moderate-to-vigorous aerobics such as brisk walking. Give your doctor a call if you need more advice on cognitive health.

Community

Community