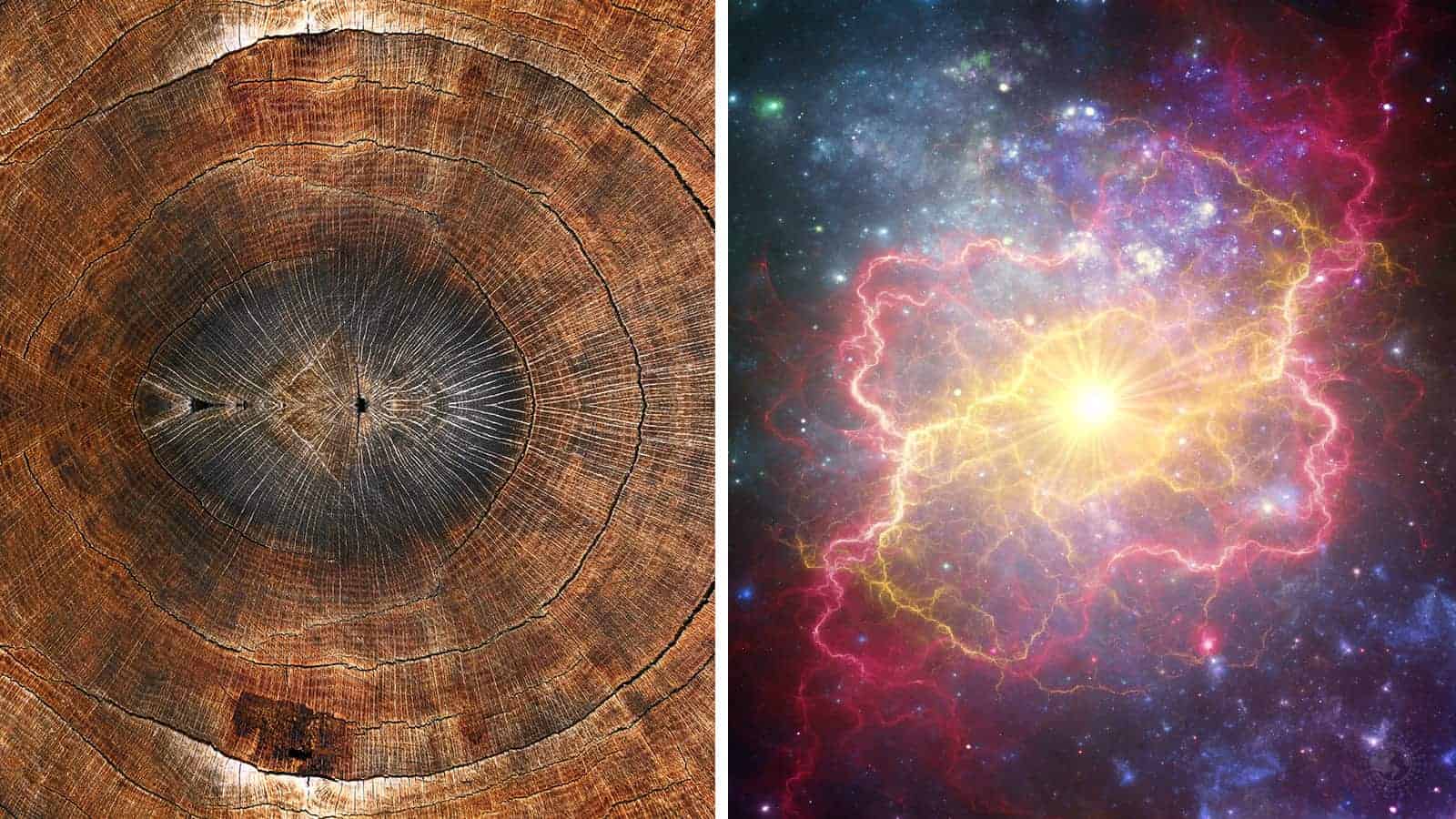

New research by University of Colorado Boulder geoscientist Robert Brakenridge shows that tree rings may hold evidence of massive space explosions. When a huge star dies off, it emits high levels of gamma radiation into the cosmos. However, these colossal explosions don’t only affect space. Additionally, they leave permanent records in Earth’s geology as well. A November 4, 2020 study in the International Journal of Astrobiology reveals that plants may keep records of these celestial explosions.

“These are extreme events, and their potential effects seem to match tree ring records,” explained geoscientist Robert Brakenridge of the University of Colorado Boulder.

The study analyzes supernovas’ effects, which astrophysicists describe as some of the most violent events in outer space. To give you an idea of the magnitude of one of these explosions, picture this. A single supernova explosion can release as much energy in a few months as the Sun does during its entire lifespan. Not surprisingly, supernovas also emit a huge amount of light into space.

Brakenridge, a senior research associate at the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research (INSTAAR) at CU Boulder, further noted the following:

“We see supernovas in other galaxies all the time.Through a telescope, a galaxy is a little misty spot. Then, all of a sudden, a star appears and may be as bright as the rest of the galaxy.”

Scientists don’t know exactly how often these supernova explosions happen in our galaxy. Various studies estimate that one to three supernovas occur each century. However, records show the most recent one exploded over 400 years ago. A supernova explosion occurring near Earth could easily put an end to human civilization. However, even if they explode farther away, the supernova can still damage our ozone layer. Furthermore, it emits dangerous levels of radiation, albeit not enough to totally wipe us out.

Scientists have a hard time spotting supernovas since their brightness varies over time. However, Brakenridge and his team thought looking a bit closer to Earth may yield some evidence of these explosions. They decided to look through Earth’s records of tree rings in hopes of finding evidence of supernovas. Their findings revealed that relatively close supernovas might have caused at least four climate disruptions on Earth in the last 40,000 years.

Radiocarbon holds the key to understanding supernova activity.

Brakenridge explained that radiocarbon, a carbon isotope occurring in only trace amounts on Earth, provides evidence of supernovas. Radiocarbon only forms when cosmic rays from outer space penetrate our atmosphere frequently. Since this radiation constantly occurs in space, Earth always gets a dose of it in varying amounts. When these cosmic rays enter the upper atmosphere, they collide with nitrogen atoms, producing a nuclear reaction which results in radiocarbon.

“There’s generally a steady amount year after year,” Brakenridge said. “Trees pick up carbon dioxide, and some of that carbon will be radiocarbon.”

However, the radiocarbon recorded in the trees varies depending on cosmic events. Scientists hypothesize that solar flares and storms may explain the random spikes in this isotope occurring over several years, then fading again. Brakenridge and his team believe these spikes in radiocarbon may occur due to much more distant space activity.

“There are really only two possibilities: A solar flare or a supernova,” he said. “I think the supernova hypothesis has been dismissed too quickly.”

The study

To test their theory, he and his team analyzed tree ring records. The first compiled a list of recorded supernovae in the past 40,000 years, as observed in remnants of stars. Next, the scientists compared this list to records of radiocarbon spikes occurring in tree rings during the same period of time.

They discovered that unexplained spikes in radiocarbon levels corresponded with the right closest supernova to Earth.

The team focused on four that stood out the most:

- The Vela supernova, once 815 light-years from Earth, exploded around 13,000 years ago. Tree ring records showed a 3 percent rise in radiocarbon around the same time. However, the Vela explosion date could have occurred 1,500 years later or earlier, as scientists can only estimate the timing.

- The 3+00.3 supernova exploded around 7,700 years ago. It once sat at a distance of around 2,300 light-years from Earth and corresponded with a 2 percent rise.

- Vela Jr. could have occurred 2,800 years ago, although scientists have a hard time pinpointing the exact time. It corresponded with a 1.4 percent radiocarbon spike.

- Lastly, HB9, which exploded 5,400 years ago at 1,000 to 4,000 light-years from Earth, caused a 0.9 percent uptick in radiocarbon.

While researchers can’t yet draw conclusive evidence from tree rings, the evidence so far seems promising. Their main difficulty lies in accurately dating the supernovae, but Brakenridge believes the findings so far warrant further research. Brakenridge said:

“What keeps me going is when I look at the terrestrial record and I say, ‘My God, the predicted and modelled effects do appear to be there’.”

If they can find more precise ways to date supernova activity, tree rings could provide great insight into these celestial events. Then, perhaps we can learn more about any supernovae that may threaten Earth soon.

Brakenridge hopes that humanity won’t have to deal with any exploding stars anytime soon. However, some astronomers think they’ve found evidence that Betelgeuse, a red giant star in the constellation Orion, might explode soon. It sits at only 642.5 light-years from Earth, which is much closer than Vela. However, no studies or findings have been published yet about this hypothesis.

“We can hope that’s not what’s about to happen because Betelgeuse is really close,” he said.

Final Thoughts on What the Tree Rings May Reveal

Scientists have found that tree rings may hold clues of past supernova activity. A geoscientist from CU Boulder believes that spikes in radiocarbon in tree rings correspond with known supernovae in the past 40,000 years. While research linking these events remains in its infancy, it could help scientists analyze supernova activity more extensively in the future.

Community

Community